This was written by the guest writer, Jasmin

Influenced by: Daoism and Onmyōdō

With this post, I’d like to start a new series in which I want to consider the use of religious tropes and images in either well-known or current Anime. Since I am a self-confessed lover of monsters and magic, this first blog contemplates the fascinating hybrid known as onmyōdō 陰陽道, and its portrayal in Sōsei no Onmyōji (2016, currently airing).

The Way of Yin and Yang

…is what a literal translation of the word onmyōdō amounts to. The hybrid nature of this (for lack of a better term) religion is already apparent from its name, which mixes Chinese and Japanese concepts.

In‘yō, as the kanji陰陽 can also be read, is the combination of yin and yang energy. These two opposites, each containing the seed of the other, and each in the process of transforming into the other, are the components and the manifestation of dao 道 (jp. dō… but more on that later). The dao is something which resists definition but amounts to a kind of world energy. Or so the ancient Chinese religion of Daoism teaches us. Its circular symbol is probably familiar to everyone, though the explanation might not be. More on the Daoist influence on onmyōdō later.

The second part of the name, 道, literally means way or path. It alludes to religion only in so far as that two other religions in Japan, which were also influenced by Daoism, use the same character: the indigenous Shintō (神道, Way of the Gods) and the syncretistic Buddhist sect of Shugendō (修験道, something like Way of Practice). However, 道 also designates various arts, from tea ceremony to sword fighting to incense-smelling to karate. It indicates a discipline which demands faithful practise over a long time in order to achieve various grades of mastery. Therefore, we can understand onmyōdō as ‘the (religious) discipline of mastering yin and yang’, and that already gives us some idea of what it (originally) entailed.

Some Background on Daoism

Lao-Tzû

One cannot pinpoint a founding date for Daoism and even the existence of a founding figure is debatable.

Concepts of an all-encompassing force (not one involving lightsabres) probably predate the oftentimes quoted sage Lao-tzû and the ancient Book of Changes (I Ching). The more magico-religious strand of Daoism even claims the mystical Yellow Emperor as its founder. However, definitions usually fall back to the works of Lao-tzû, since he is the closest thing to a reliable source 😉

“Lao-tzû tells us that Tao (Way) is just a convenient term for what had best be called the Nameless. Nothing can be said of it that does not detract from its fullness. To say that it exists is to exclude what does not exist, although void is the very nature of the Tao. To say that it does not exist is to exclude the Tao-permeated plenum. Away with dualistic categories.”[i]

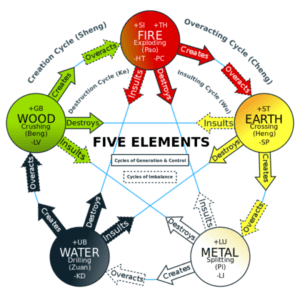

Five Elements

Another important aspect is the idea of constant change occurring in repeating patterns, such as the seasons in nature. Here another concept bears introduction: namely, the five phases or elements. Wood feeds Fire, Fire’s ash fertilizes Earth, Earth contains Metal, Metal attracts Water (as in condensation), and Water nourishes plants, that is, Wood. In this fashion, the elements form a circle. If you now consider which element conquers or destroys another, you get diagonal lines crossing the circle: A Wood plough conquers Earth, Earthen dikes beat Water, Water extinguishes Fire, Fire melts Metal, Metal chops Wood.[ii] A pentacle appears inside the circle, and this pentacle still appears in places associated with onmyōdō in Japan, such as the Shrine of the most famous Japanese yin-yang magician, whom we’ll discuss later.

Daoists’ goals and means

So, what did Daoists want? Superficially, magical powers seem valid objectives, and feats such as invulnerability, prolonged life and youth or the ability to expel demons or foretell the future all have been attributed to Daoist adapt of the ancient and recent past. These powers, however, are only secondary to the true believer, who aims to become one with the Dao and, for example, simply needs to live a very long life in order to achieve this.[iii]

Meditation and Outer Alchemy

Several methods to prolong life existed. Once could make use of breathing techniques and meditation to manipulate the energies within one’s own body, so that drops of a mystical essence ascended to one’s crown. Alternatively, one could experiment in a more commonly alchemical way with specific (often toxic) ingredients to create the ‘Golden Pill’ or ‘pure essence of spirit’, which would not only confer immortality but also transform base metals into gold… so yes, Daoism has its own philosopher’s stone.

Sexual Alchemy

One can read some alchemist texts, such as the Ts’an T’ung Ch’i mentioned by Blofeld, as tantric manuals, where the union of yin and yang means sexual union.[iv] This type of ritual involves careful control of movement, breathing and rhythm. It also hinges on the male adept avoiding ejaculation since that amounts to a loss of precious yang energy, the “ultimate goal [being] the production of an embryo of a perfect being” through the union of yin and yang inside one’s body.[v] This perfect embryo seems to me to be just another image, like of the golden pill of outer alchemy or the holy drops of mysterious essence produced by meditation and energy control. It seems merely a symbol of perfection attained by religious practice. However, the series Sōsei no Onmyōji may be taking this a bit more literally, as I will discuss below.

Onmyōdō isn’t Japanese Daoism

One additional, astonishing aspect of Daoism I would like to mention: as recounted by Blofeld, an intense pacifism permeates of the whole exorcism business. “One does not like to destroy genuine demons except as a last resort. They love their lives as much as we do and have the same rights to existence”, he let one of his characters say.[vi] In many portrayals of Japanese onmyōji, by contrast, they do not treat demons this kindly. However, even in Daoism, curse-created sprites are an exception. They have “no life to lose, being a mere extension of the magician’s mind.”[vii] Such a creature born of evil intent is a curse taking physical form; and this concept is a staple of onmyōji lore – mostly presented as shikigami, which we’ll come back to later.

Indian and Chinese religion and philosophy entered Japan via the Korean kingdoms from the fifth century AD. But whereas Buddhism became prominent in the country’s power struggles, and experts, texts and statues were imported from China to furnish Japanese Buddhist monasteries, there is no clear evidence for any attempt to install organized Daoist religion in Japan. Instead, its texts and concepts, methods and deities were appropriated in Buddhist and Shintō contexts.[viii] Thus evolved the Japanese magical religion called onmyōdō, with onmyōji as its practitioners and “priests”.[ix] In the medieval Japanese state, these specialists had a well-defined set of tasks to perform; they were courtiers and officials in addition to their quasi-priest role.[x]

The “Golden Age”: Court Onmyōji and the Divination Office

The Japanese government of the Heian era – the “high middle ages” of Japan, origin of much of its classical literature – was built to resemble Chinese models and employed complex ranking systems. It is thanks to these rankings and the lists needed to keep track of them that we know about the organization of the official court onmyōji.[xi] The Yin-Yang-Office (onmyōryō) “was set up to handle affairs in the four areas of yin-yang-cosmology, astronomy, calendar calculation and time keeping”.[xii] The four fields, despite being assigned specialist “doctors”, are intertwined. Yin-Yang and Five-Phase thought pervades the calendar and time settings with twelve animals, which also double as star signs.

It comes as no surprise than that astrological divination was used to determine fortunate and dangerous days for each year’s calendar, and the directions (each linked to an element) one needed to avoid every day. In addition, Heian court intrigue might cause supernatural retribution, from which one needed protection. This was also a task of the onmyōji, who could divine the origin of an ailment and exorcise the demon or repel the curse which caused it. In addition, they performed Daoism-inspired rituals for the longevity of aristocrats.[xiii]

Shikigami

Possibly the first magical tool we now imagine in the hands of an onmyōji is the shikigami (式神/識神). It is most commonly depicted as a paper effigy which, once infused with spiritual power, transforms into a monster-like entity and does the caster’s bidding. However, onmyōdō texts do not even mention them.[xiv]

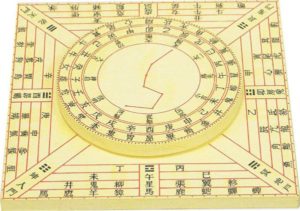

The name itself is ambiguous; shiki can be written as either “ritual” or “consciousness”, whereas kami, here written as “god“” is a homophone of 紙, “paper”. So, this is paper is infused with the caster’s conciousness or will in a ritual, which acts as a supernatural being. Japanese language is so much fun! Anyways. Divination using the shikiban, a two-piece divination board with inscriptions referring to yin-yang, calendrical animals, and the I Ching hexagrams, makes use of 12 Guardian Deities of the months, in the “heaven” half. Seimei allegedly made these his shikigami. Alternatively, he commanded two very powerful ones, each representing one realm of the board (earth and heaven).[xv]

Initially, though, Shikigami may have been a mere divination technique.[xvi] The foretelling of future ills through the shikiban may have involved a god of the shiki-board, a shiki-gami. This entity then became the means of inflicting, rather than the announcer, of misfortune. Thus, the shikigami as manifestation of a curse was born. In turn, an onmyōji could recognize the occurrence as an action of an enemy magician and repel the curse. The caster then dies of his own rebounding spell. This technique was another specialty of Seimei’s.

The ambiguity of the shikigami may be best summarized in Pang’s words: “the shikigami is actually a means through which the onmyōji controls the innate energy in natural elements with magical incantations.”[xvii] This fits all aforementioned manifestations.

Abe no Seimei as Ideal and Prototype

Abe no Seimei is the most famed and, legend has it, most powerful onmyōji of all time. Some tales claim his mother was a kitsune, a magical fox spirit, [xviii] because this power seems inconceivable for a mere human being. However, he did not do his deeds in a vacuum, but rather represents the craft as its most prominent practitioner. Onmyōdō was an institution of the Heian-era Court, as I mentioned above.

The historical Seimei, or Haruaki, as his name would have been read prior to his popularity, was initially a court official of mediocre rank.[xix] It was his aptitude at performing the tasks expected of an onmyōji, combined with a long life, that enabled his rise to high rank and office, as Shigeta delineates. Seimei’s repertoire included purifying buildings before use, summoning rain, explaining occurrences, divining fortunate days, performing healing rituals, and repelling curses. For the effectiveness of his rituals he received promotions.[xx] Shikigami, however, are not even mentioned in regard to him in any of the official sources.[xxi]

From the Middle Ages to the Early Modern Period and Beyond

Since that time, the Abe clan and (being pushed to second rank after Seimei’s success) the Nara-based Kamo family were the traditional onmyōji linages, until the extinction of the latter. In the Edo period, whoever wanted to perform divination, no matter his or her religion or self-description needed a certificate in order to do so. These certificates were granted by the Tsuchimikado family of onmyōji: the descendants of the Abe line.[xxii]

From this we can see how far onmyōdō departed from its Daoist influences and transformed to satisfy the demands of Heian-era court nobility, and yet, how it survived to the early modern period. Meiji’s emphasis on western scientific thought brought the practise to an end. But in the 1990s, onmyōdō celebrated a sort of revival in the Abe so Seimei-Boom caused by Yumemakura Bakus Onmyōji novels. Its numerous appearances in popular culture until now then can probably be traced back to this event. Anime series such as Kekkaishi and Mononoke draw on onmyōdō lore without naming it, whereas a monster-focused tale such as Nurarihyon no Mago casts onmyōji (initially) as antagonists. The most extensive focus on onmyōdō I know of, however, is this year’s Sōsei no Onmyōji, “Twin Star Exorcists”.

Sōsei no Onmyōji – Twin Star exorcists

Names

Sōsei no onmyōji takes up a number of the abovementioned symbols and concepts. The title hints at the importance of astrolog, and the chief onmyōji, Arima, performs divination. He bears the historically correct title, onmyō no kami.[xxiii] In addition, his family name, Tsuchimikado, reveals his descent from the Abe family. The two main characters also have names which allude to historical onmyōji or sites of magical ritual. Enmado Rokuro may be named for Roku Emaro, a seventh-to-eighth-century “doctor of onmyōdō” from the continent who was commanded to renounce religious orders and found a dynasty.[xxiv] Adashino Benio’s surname maybe alludes to the Adashino temple near Kyōto, which celebrates a ritual for uncared-for souls (a raw material for monsters) every year.[xxv]

Monsters…

The series’ exorcists main task is to exterminate monsters called kegare. Usually, the noun kegare refers to abstract spiritual pollution rather than a monster-type entity, though. Therefore, the whole business of exorcists can be interpreted as a sort of metaphorical exorcism. However, despite the intelligence and emotion evidenced in higher forms of kegare, onmyōji do not grant them mercy and a right to exist, as Daoist exorcists might have done. Instead, two high-ranking onmyōji exterminate a very touchingly human kegare in what amounts to one of the most tragic moments of the series. Among the exorcists’ skills, shikigami feature regularly, most prominently in Benio‘s pet fox (who however does not seem to have any fighting properties). Head onmyōji Arima uses one as a replacement for himself, and commands two immensely powerful fighting shikigami, in a call-back to his ancestor.

…and Spells

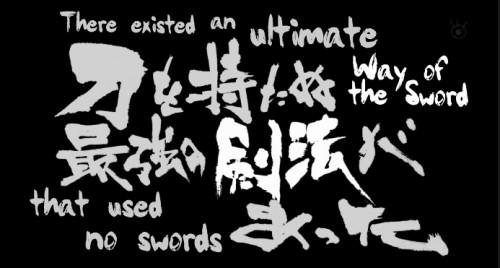

When calling forth enchantments on body and weapons, these exorcists use a genuine Daoist spell, 急急如律令[xxvi] (kyūkyū nyo ritsuryō, if read in Japanese), though the type of application shown in the anime is, to my knowledge, original. Additionally, Benio’s swordplay calls to mind “a Chinese discipline that utilized swords and magic spells to exorcise evil spirits”[xxvii] mentioned in the context of Daoist imports, though I could not confirm the use of the aforementioned spell in this art.

Exorcism in the classical sense also features strongly in the second arc of the series. Whenever portals to the Magano (the demon realm) open, the vapours sicken the human population of the surrounding area, who then need the assistance of onmyōji. Healing requires purification spells, perhaps an allusion to the longevity rituals of Heian court onmyōji but surely a part of the exorcists’ basic task, erasing impurity. The most impressive cleansing, however, is an early use of the main characters‘ special power or “resonance”: With their joint energy, they manage to return a friend to normal after she transformed into a kegare, using the supreme purification spell – a feat previously considered impossible.

Heavenly Guardians

The 12 Heavenly Guardians of the shikiban, the legendary shikigami of Seimei, also appear in the series in the form of the 12 most powerful exorcists, who directly serve Tsuchimikado Arima, Seimei’s heir. Each of them bears the title of one of the twelve and has corresponding abilities. This fits with Pang’s view of shikigami as, ultimately, a kind of energy to be manipulated by those capable of the feat.[xxviii] Those who have enough spiritual energy, that is, in this series.

What makes protagonists Rokuro and Benio stand out is not so much their individual power. Although they are considered strong, especially for their age, they are repeatedly shown to be massively inferior to other characters. Their potential lies, in the first part, in their capability of “resonance” or joining their (male and female?) energy. In the second arc, however, even with resonance they are clearly outmatched by evolved Kegare (Basara) and Guardians alike. This seems to suggest that, after all, it will be not their resonance but their child, the Miko of the prophecy, who saves the world.

Miko – Child of Prophecy

In the second episode, Arima reveals the backstory of the series’ title. He claims to have received an oracle telling him about the immanent appearance of the Miko, the divine child foretold to end Magano and free the world of kegare monsters. The Miko is the child born of the Twin Star exorcists, as whom he has divined Benio and Rokuro, to the annoyance of both. This idea reminds me of the concept of the perfect child conceived by Daoist adepts in a ritual of sexual alchemy. This being „controls and registers the multitude of spirits. Summoning them by name according to the Registers, he lets none of them escape.”[xxix]

Summoning by name seems to be an important phrase: exorcist techniques have to be called by name – they are essentially spells – and individuals are painstakingly introduced with their name, displayed in a freeze-frame next to their face. It might just be an anime staple, but I would like to see it practically applied in a story-relevant manner. For example, the Miko, if she[xxx] is eventually born, might call all the Basara by name and purify them in that way.

A Theory

Alternatively, perhaps the two energies the Miko is going to unite are not Benio and Rokuro’s female and male spiritual energy. With their kegare-infected arm and legs respectively, both heroes harbour in themselves some kegare-aspect, the same way the white and black halves of the yin-yang-symbol contain a drop of its opposite. Similarly, Basara have clearly human features, despite their exaggerated cruelty. It stands to reason that the elimination of Magano, which is the final goal of the exorcists, is as unreachable as the Basaras’ aim to take over reality. “Away with dualistic categories!”, as Blofeld put it.

I have the theory that the child of Rokuro and Benio might be a natural human-kegare hybrid and that she will end Magano by fusing it with reality, releasing both kegare and exorcists from their fate – by annihiliating the magic energy they work with. I don’t think she will make anyone immortal or produce gold, though ;).

Notes, References, and Image Sources

[i] Blofeld, John. Taoism. The Quest for Immortality. London & Boston: Unwin Paperbacks, Mandala series, 1979, available online https://de.scribd.com/doc/204085686/John-Blofeld-Taoism-The-Quest-for-Immortality. As an introduction, another of his books on Taoism, such as The Secret and the Sublime (1973), also makes an interesting read. For an introduction to the more philisophical aspects of Daoism, see http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/daoism/.

[ii] see Watts, Alan. Tao, the Watercourse Way (1975), which I read in the German edition, so I omit page numbers.

[iii] Again elaboreated by Blofeld, esp. in Taoist Mysteries and Magic (1983), where he condenses his experiences with different stands of Taoism into interesting if ficticious accounts. It seems our univerity librarian had a liking for his books 😉

[iv] cf. Blofeld 1979.

[v] Mollier, Christine. „Conceiving the Embryo of Immortality: ‚Seed-People‘ and Sexual Rites in Early Taoism“. In: Andreeva, Anna & Dominic Steavu. Transforming the Void. Embryological Discourse and Reproductive Imagery in East Asian Religions. Leiden & Boston: Brill, 2016. 87-110. 90.

[vi] Blofeld 1983:80.

[vii] ibid.

[viii] Concerning this, see also Hayashi Makoto & Mathhias Hayek, „Editor’s Introduction: Onmyōdō in japanese History“, Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 40.1, 2013, 1-18. 5-6.

[ix] For an in-depth description of the reception of Daoism in Japan, see Masuo Shin‘ichirō, „Daoism in Japan“, in Kohn, Livia (ed). Daoism Handbook. Leiden: Brill, 2000. 821-42.

[x] See Masuo Shin’ichirō, „Chinese Religion and the Formation of Onmyōdō“, Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 40.1, 2013. 19-43.

[xi] Masuo 2013.

[xii] Masuo 2000:824.

[xiii] Masuo 2013:35.

[xiv] Pang 2013:100.

[xv] Pang 2013:104.

[xvi] An argument made by Pang, Carolyn, „Uncovering Shikigami. The Search for the Spirit Servant of Onmyōdō“, in Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 40.1, 2013, 99–129.

[xvii] Pang 2013:110.

[xviii] Pang 2013:117-8.

[xix] Shigeta Shin’ichi. „A Portrait of Abe no Seimei“. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 40.1, 2013, 77-97. 78; 87.

[xx] Shigeta 2013, esp. 84.

[xxi] Shigeta 2013:93.

[xxii] Discussed in detail by Hayashi Makoto, „The Development of Early Modern Onmyōdō“, Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 40.1, 2013, 151-67.

[xxiii] Masuo 2013:22.

[xxiv] Masuo 2013:26.

[xxv] As mentioned in this Japanese-language documentary.

[xxvi] Masuo 2000:824.

[xxvii] Masuo 2013:21.

[xxviii] Pang 2013:109-10.

[xxix] Translation of a Daoist manual in Mollier 2016:91.

[xxx] The sex of the child is unknown, but since Shintō shrine maidens are called miko even today, I have a feeling it might be a girl. In any case, there is no reason to assume it has to be a boy (except the tendency of action anime to sideline women, but here we have at least a male and a female protagonist, so hopes may be entertained, I dare to hope ;))

Image sources in order of appearance:

yingyang: https://image.freepik.com/freie-ikonen/yin-yang-ios-7-symbol_318-34386.jpg

Laotzû Statue: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/dd/Statue_of_Lao_Tzu_in_Quanzhou.jpg

5 Elements: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wu_Xing#/media/File:FiveElementsCycleBalanceImbalance_02_plain.svg

Shikiban: http://www.onmarkproductions.com/html/slideshows/rikujinshikiban-master.jpg

Seimei photo: my own archive.

Twin Star Poster: https://myanimelist.cdn-dena.com/images/anime/3/77328l.jpg

Purification Spell: https://josefcd904.files.wordpress.com/2016/09/twin-star-23-11.png?w=736

Benio’s legs: http://65.media.tumblr.com/7e67877a73df6a19068251c32c83e809/tumblr_oc34dm5WAy1vysie1o1_1280.png

Samurai’s Deepest ( Repent ). :-

As I Stand On My Feet……….

As i stand on my feet, On the ground’s benet……, * ME *.

And as i tried to feel the cooled * Winter’s* breeze.

But i feel like i’ m locked in a far ” far distant choir,

Inside a cage… Dark Pitch Black, like there’s nothingness in the Air * Any-More….*

( IT’S LIKE I CAN’T EVEN FEEL ANYTHING )*

( NOTHING… ANY – MORE…..)*

( AND MY EYE’S CAN’T SEE NOTHING ANY – MORE …..)*

” But this sweet and joyful sound echoed in…. My Ear’s. ”

And it brought such sudden JoY and HappiNess in me, It Melt My Merciless & In-pure Heart.

Because of such sudden Joy & Happiness, that it reminded me…..*

That i am still ” Alive ….., And My Life is Still Worth Awhile ……*

*( Maybe I’m Dead OR I Look Dead From Out ~ Side ….)*

*( But Still I’m Breathing & Trying To Live From In ~ Side ….)*

It’s Rather Funny ……, ” That I Must Say… ”

It’s Because 0f What I Had Done In The Past, I Regret And Coz 0f that i curse my-self…

” 0f Creating such Crimes such Sin’s… ” ***But Still….. ”

*** I still seem to Smile. *** …..Yes….. *** I still Smiled *** & *** I still Smile…….

# But yet I don’t even know ” Why “. # And *** Theo I don’t even know ” How “.

***( Can I Even Give A Happy Smile )..?

If I could give and show Even A Little Bit ….. 0f Happiness ***….. ,

Then ” I could ” 0R ” Could I “., ** Repent for all the Sin’s I had done.

***# So As I Wonder #***………,,,

*** As I Stand On My Feet ***

And : —

*** On The Ground’s Benet ***

***THE

END***