Anime and manga are a style of their own, just like Cubism or Pointillism. Some people lump anime into the “Superflat” art movement because of the flat nature of anime art. But whatever you want to call it, anime is valuable. Back in 2001, animation cells from the anime Princess Mononoke– animation cells were once thought to be trash–sold for thousands of dollars (Watson, 2001).

Anime storytelling roots extend far back in Japanese art, but the years after World War II marked the beginning of anime as a storytelling medium. Unlike American cartoons, anime focuses on realism in image and movement. This realism started with the “God of Anime” Osamu Tezuka. Tezuka wrote over 150,000 pages of story, covering every genre and age group (Watson, 2001). He set the groundwork for anime’s breadth. In contrast, most animation in the United States is produced for and watched by children (Halsall, 2004).

Themes of Anime

“Anime is complex and multifaceted, fabulous storytelling combined with extraordinary animation.”

The wide appeal of anime makes it hard to define, but anime stories typically follow the following themes (Halsall, 2004):

- Technology (or magic) vs. humanity.

- Problems of technology (or magic) vs. whatever is trying to destroy the world or city.

- Good vs. Evil. In a person or in a society.

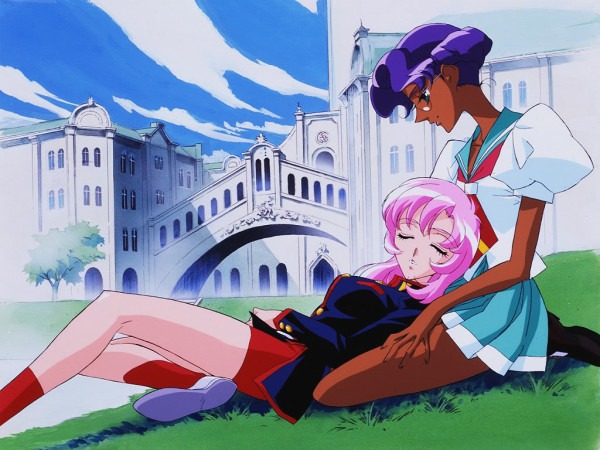

- Rite of Passage. A child growing to adult or a person becoming a better, healthier person.

- The challenge of living with other people.

However, anime is more than its stories. Anime is a medium, a tool for stories. A medium conveys information. Oil painting is one type of medium. Comic books are another. The techniques of anime– its flatness, large eyes, animation style–are similar to the composition, paints, and techniques used to make paintings. Lately, we’ve seen anime turned into live-action movies. Attack on Titan is one example. Story and medium (the word media is the plural of medium, similar to datum and data) are separate. Attack on Titan isn’t an anime, it is a story that happens to use anime as its medium. This sounds nitpicky, but the distinction is important. Stories can be shared across many different media. A book can become a movie, inspire a painting, or become a comic book. Each medium has strengths and weaknesses that affects how the story works.

Many people, myself included, have problems with “anime.” But it isn’t anime we have a problem with. It is the stories that ruffle us. Many of the stories in anime are poorly paced and told. However, this has little to do with anime as a medium. Live-action has poor storytelling too. A poor story dressed up with blockbuster actors or excellent, vibrant animation is still a poor story. Now, I am not saying anime doesn’t influence stories. Every medium has limits. A live action movie can’t portray the outlandish things drawn media can. That is why movies rely so much on computer animation for transforming robots and creating vast environments. But no matter how shiny the special effects or how well known the actress, a poor story is a poor story. The medium can’t save it.

Anime’s Strengths and Weaknesses

This makes the death of characters in anime crash down on us. They are dead in a stark, final way. Sure we can rewatch the series or write fan fiction, but when a character dies in anime or the series ends, the character will not appear again. Movies envy the finality of an anime character’s death. Even characters that live on, the finality of the viewer’s parting with them can’t be matched by movies. Samurai Champloo‘s ending is a good example of this wistful parting of character and viewer. This is the greatest strength of anime’s storytelling.

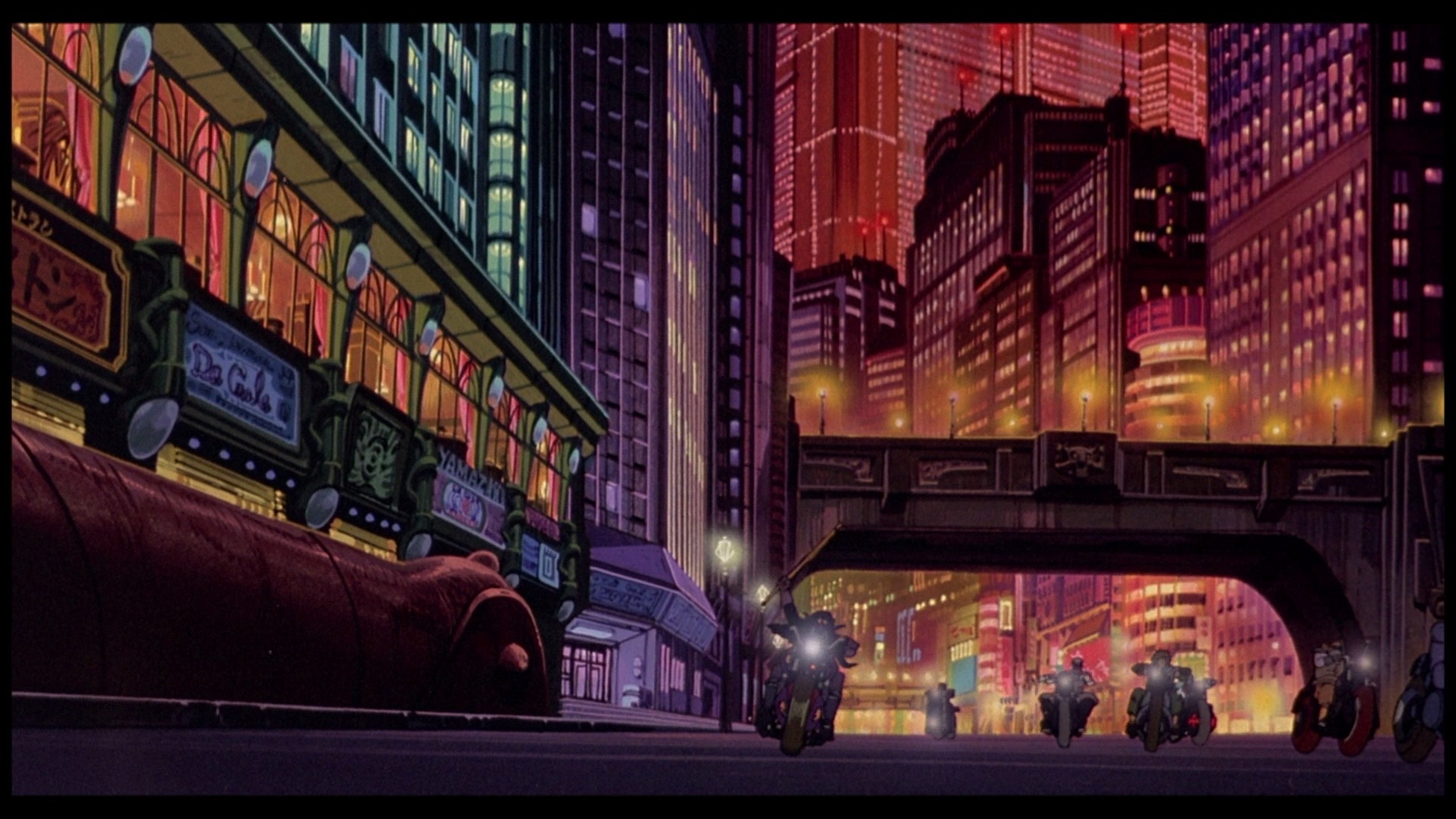

Because it is a drawn medium, anime tells stories that requires live-action to splurge on special effects. Think about the Lord of the Rings movies and their extreme sets and computer animation. Middle Earth took a lot of effort to create on the screen. Contrast this with what a painting can do. Anime enjoys the “suspension of disbelief” that movies have to work at achieving. Because movies feature living people, we have to stretch our ability to believe what we see. However, anime, because it doesn’t seek to replicate reality, enjoys more leeway. We can believe weird stuff when it is drawn easier than if it was live. We expect reality– and anything that looks real–to behave in certain ways. Violating those ways can shock us out of a story. Books and movies have to work hard at building worlds that can have odd stuff, like magic, without shocking us out of the story. Anime and comics can blast us without too much worry.

Anime’s techniques contains its weakness…at least for America. Because Americans associate animation with childhood, anime has limited appeal. And this limited appeal limits the type of stories that make it to the United States. Teens and twenty-somethings dominate anime’s US audience. This means companies send stories that appeal to this limited audience. This forces the medium into a niche that has proven difficult to escape. In turn, this also encourages lower quality storytelling. Expansive adult stories, like Ghost in the Shell, are rare because American adults are not socialized to view anime as a valid storytelling medium.

Certain stories fit best in certain media. The elements of the story may be best handled by the techniques of a certain medium. Take Lord of the Rings. Because of the themes and general believable nature of Middle Earth, the story favored movies. There is a bad cartoon of The Hobbit. Now, imagine One Piece as a movie. I really can’t see the odd world translating well to live-action. It would lose what makes One Piece One Piece.

The main point to take away from this is the separation of story and medium. Anime isn’t the stories. Anime is the method of telling those stories.

References

Halsall, J. (2004). The Anime Revelation: How I Learned to Love Japanese Animation and Changed Our Teen Video Collection Forever. School Library Journal, 50(8), S6.

Watson, L. C. (2001). Japanimation: breaking down the boundaries. Art Business News, 28(4), 72-74.