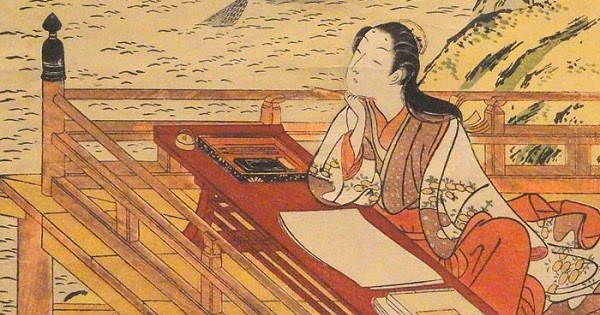

Murasaki Shikibu wasn’t her name. Like many female writers in history, we don’t know her real name. Murasaki, however, is a nickname derived from her greatest work The Tale of Genji. She lived during the Heian period, a cultural flowering period in Japan between 794-1192. She was a contemporary with Sei Shonagon and Akazome Emon, two of the greatest female writers of the period. Murasaki lived at a time when phonetic Japanese was still being developed. The Tale of Genji and her diary helped develop the foundation for modern Japanese hiragana and katakana (Bowring, 2005).

Murasaki was born sometime in 973 to a lower branch of the Fujiwara family. Her father, Tametoki, made sure she was well educated so she could continue the family’s educational traditions. Tametoki specialized in Chinese literature. Murasaki had at least one brother. She married in 998, and she eventually birthed a daughter who also write and compiled poetry, to follow the family tradition. We don’t know exactly when Murasaki died, but the best estimates place her death around 1025, although she may have lived well beyond that year. That is just when she disappears from the scanty historical record.

What we have of her diary is a fragment of a larger work. According to Bowring (2005), Akazome Emon uses a larger text as a reference for her own work A Tale of Flowering Fortunes. However, Emon removes the personal thoughts of Murasaki. At times, Flowering Fortunes overlaps with fragments from the diary and offers expansions in what appears to be Murasaki’s voice. Murasaki’s surviving diary details her observations of court life starting with the birth of the next emperor. The diary includes often extreme details of clothing and rituals. Despite working as a lady-in-waiting and a tutor, Murasaki is an outsider by rank and by temperament. Throughout the diary, she appears withdrawn, stifled, and melancholic because of the structure of the court.

Similar to Sei Shonagon’s Pillow Book, Murasaki’s diary focuses on court gossip and politics. However, as I read the work, I sense an exhaustion with the court that Murasaki will later put into a letter. Whereas Shonagon never delves into self-reflection, Murasaki often does. This passages glow with personality and show a sharp mind stifled by society:

There is also a pair of larger cupboards crammed to bursting point. One is full of old poems and tales that have become the home for countless insects which scatter in such an unpleasant manner that no one cares to look at them anymore; the other is full of Chinese books that have lain unattended ever since he who carefully collected them passed away. Whenever my loneliness threatens to overwhelm me, I take out one or two of them to look at; but my women gather together behind my back. “It’s because she goes on like this that she is so miserable. What kind of lady is it who reads Chinese books?” they whisper. “In the past it was not even the done thing to read sutras.” “Yes,” I feel like replying, “but I’ve never met anyone who lived longer just because they believe in superstitions!” But that would be thoughtless of me. There is some truth in what they say.

Each one of us is quite different. Some are confident, open and forthcoming. Others are born pessimists, amused by nothing, the kind who search through old letters, carry out penances, intone sutras without end, and clack their beads, all of which makes one feel uncomfortable. So I hesitate to do even those things I should be able to do quite freely, only too aware of my own servants’ prying eyes. How much more so at court, where I have many things I would like to say but always think the better of it, because there would be no point in explaining to people who would never understand. I cannot be bothered to discuss matters in front of those women who continually carp and are so full of themselves: it would only cause trouble. It is so rare to find someone of true understanding; for the most part they judge purely by their own standards and ignore everyone else.

So all they see of me is a facade….

By the time you get to the above passage, you’ve seen the politicking and gossip that goes on in court. This section isn’t angst. It is exhaustion and frustration. Most of the time, Murasaki writes favorably, or at least charitably, about the people around her. She often expresses concern for some of those who serve in the court with her. She even writes about Akazome Emon and Sei Shonagon:

The wife of the Governor of Tanba is known to everyone in the service of Her Majesty and His Excellency as Masahira Emon [Akazome Emon]. She may not be a genius but she has great poise and does not feel that she has to compose a poem on everything she sees, merely because she is a poet. From what I have seen, her work is most accomplished, even her occasional verse. People who think so much of themselves that they will, at the drop of a hat, compose lame verses that only just hang together, or produce the most pretentious compositions imaginable, are quite odious and rather pathetic.

Sei Shonagon, for instance, was dreadfully conceited. She thought herself so clever and littered her writings with Chinese characters; but if you examined them closely, they left a great deal to be desired. Those who think of themselves as being superior to everyone else in this way will inevitably suffer and come to a bad end, and people who have become so precious that they go out of their way to try and be sensitive in the most unpromising situations, trying to capture every moment of interest, however slight, are bound to look ridiculous and superficial. How can the future turn out well for them?

As you can see, Murasaki thought highly of Emon but not of Shonagon, yet she also retains equanimity toward Shonagon with a worry about how Shonagon causes herself problems. Throughout the diary you see this balance. She never labels anyone all good or all bad. In fact, she expresses this idea in several places, and, if you’ve read the Tale of Genji, you see it in her work.

Although Murasaki gets the name we remember her by from a character in The Tale of Genji, this isn’t a modern development. She records an instance in her diary where she is called by that name:

Major Counselor Kinto poked his head in. “Excuse me,” he said. “Would our little Murasaki be in attendance by any chance?”

“I cannot see the likes of Genji here, so how could she be present?” I replied.

Interestingly, Murasaki mentions reading drafts of The Tale of Genji to the court and some of the drafts even disappearing, taken by the Emperor himself. Already, people couldn’t wait to read the next installment of her work:

Nevertheless, from time to time he [the Emperor] would bring her good thin paper, brushes and ink. He even brought an inkstone. When the others found out that Her Majesty had given it to me, they all complained loudly. I had obtained it by going behind their backs, they said. Despite this, she made me another present of excellent colored paper and some brushes. Then, while I was in attendance, His Excellency sneaked into my room and found a copy of the Tale that I had asked someone to bring from home for safekeeping. It seems that he gave the whole thing to his second daughter. I no longer had the fair copy in my possession and was sure that the version she now had with her would hurt my reputation.

Thankfully, Murasaki either gets the copy back eventually or rewrites it. She mentions several more times about the Emperor and others wanting to read the Tale as she called The Tale of Genji. The Emperor and Empress supports her work, much to the jealousy of some of the other women as this passage mentions. You can see why Murasaki complains a little in the letter section of her diary. Throughout the diary, she voices frustration with the social aspects of the court and how she can’t be left alone to pursue her work. Other times, she comments how she feels lonely because of how her “dreariness” puts others off of her. Murasaki’s self-reflection gives you a sense of who she was. It truly feels as if you are reading a diary, unlike the intended-for-public Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon.

Murasaki is often hard on herself as self-reflective people tend to be. She is a people watcher, which pays off in her Tale of Genji. I find her personality likeable. She is depressive at times, but not one to “completely abandon herself to despair.” Like me, she is exhausted by people and sometimes hides to avoid them. She is personable despite 1000 years separation. It’s unfortunate the diary we have is fragmented. Even translated, her prose shines. We can hope more fragments of her larger diary will be discovered, so we can learn more about her life and thoughts.

Reference

Bowring, Richard (2005). Trans. The Diary of Lady Murasaki. London: Penguin Classics.

If Genji’s beloved Murasaki is indeed Murasaki Shikibu’s alter ego, then Shikibu certainly saw her own life as the manufactured product of an isolating courtly tradition. “So all they see of me is a facade…”

To some extent, there are perhaps parallels with Empress Masako Owada’s admission that she has had to struggle with life in Japan’s current court. On one hand, these women were afforded a worldly education along with the time and resource necessary to develop the wisdom to consider the value and meaning of a life. And yet, they were (are) still constrained by the traditional duties of that same privilege.

The perhaps nihilistic paradox of wisdom is to become aware of our constraints, to live in the shadow of what we know, that even a full life is brief and passes mostly unnoticed. “…I have many things I would like to say but always think the better of it, because there would be no point in explaining to people who would never understand.”

Makes me wonder what Murasaki Shikibu would have thought if she could have known that her thoughts would be shared by people around the world a millennium into the future.

I sympathized with Murasaki’s facade. When I would rather be quiet and be left alone, I must wear a sociable mask. Murasaki’s diary has many parallels with Lady Nijo’s Confessions.

Perhaps Murasaki would’ve been comforted to know many other people would identify with her thoughts and understand her frustrations.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts!