Tales of Ise is referenced throughout early Japanese literature. If you hadn’t read it, you won’t catch some of the meaning Sei Shonagon, Lady Nijo, Murasaki Shikibu, and other writers make through their references. Tales of Ise is a collection of 209 short stories and anecdotes written and collected somewhere between 850 CE and 950 CE. Murasaki in The Tale of Genji calls it a classic.

Tales of Ise contains work from many unknown writers. However, we do know the name of one: Ariwara no Narihira (825-880). Narihira was a bureaucrat, poet, and well-known lover. Throughout Tales Narihira appears to be a real-life Prince Genji. A passage in Tales gives us this idea: “Most men show consideration for the women they love and ignore the feelings of the ones who fail to interest them. Narihira made no such distinctions.” Most of Tales of Ise focuses on courtly love. However, we know Narihira wasn’t the only author because of the differing writing styles and the fact his jisei, or death poem, is included in Section 125:

Once a man [Narihira] was taken ill. Sensing the approach of his death, he composed this poem:

Upon this pathway,

I have long heard it said,

man set forth at last–

yet I had not thought to go

so very soon as today.

Tales of Ise was seen as an example of how a sensitive courtier was supposed to behave, particularly toward women. However, I have to say for us modern readers, some of the behaviors may be troubling or offensive, such as this poem about love between brother and sister:

Once a man who was stirred by the beauty of his younger sister composed this poem:

It pains me to think

that another hand will bind

the young grasses–

the herbs so fresh and tender,

so ideal for sleeping.

She replied:

Why do you speak of me

in words as unfamiliar

as the sight of young grass

when springtime comes? Have I not

loved you in all innocence?

Most of the collection feels like you are reading the romances of medieval Europe. You will see unrequited love, adultery, painful poems of longing, and expressions of love between husband and wife. Like the medieval romances, poetry dominates the work. Tales of Ise shows how certain images where already established in Japanese literature, such as cherry blossoms, wet sleeves, autumn leaves, spring grasses, and other nature symbols. As I read the work, the melodrama of crying into sleeves became cliched. When you read later Heian literature, such as The Tale of Genji , you will see these cliches too. It seems Tales popularized these turns of phrases. It seemed all people did was cry at everything back then! Of course, this literary turn-of-phrase was meant to express the sensitivity of people. In fact, this sensitivity laid the foundation for one of the major themes in Japanese literature: impermanence.

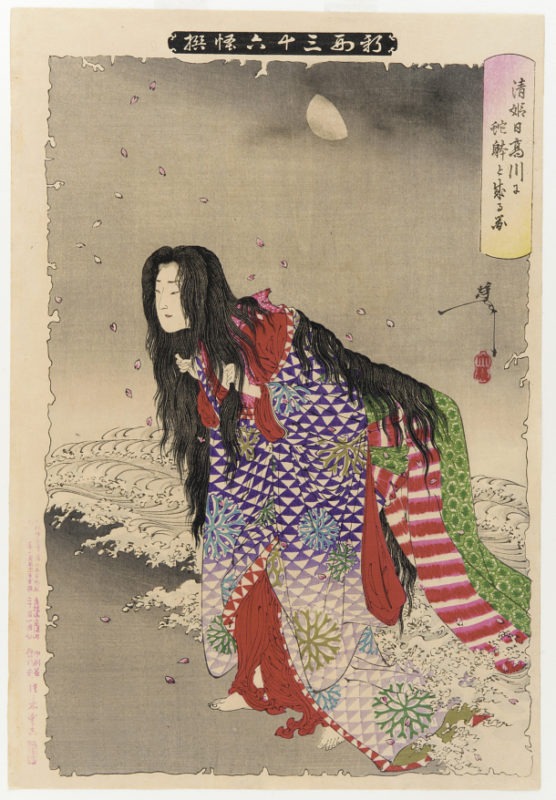

Impermanence is the realization that everything in life is temporary. Buddhism embeds this realization, and Japanese culture embraced it with its most iconic and beautiful symbols. Cherry blossoms, for example, exist for only a short time each spring. Watching the moon is only a single moment in time. Even the tea ceremony embraces the one-time, unrepeatable moment in time. In Tales of Ise‘s descriptions of love, we also see this idea of impermanence. For example:

Once a man [thought to be Narihira] sent word to a woman, “I’ll die if things go on like this.” She answered:

If the white dew

must vanish, let it vanish.

Even if it stayed,

I doubt that anyone

would string the drops like jewels.

The man considered the reply most discourteous, but his love for her increased.

In the passage, the unnamed woman recognizes how their love was temporary and suggests she had already moved on. Their love was as impossible as stringing dew into a necklace. She embraced the idea of impermanence while Narihira didn’t accept it. Of course, her coy response was also part of the language of courtship at the time. This double layer of meaning (coyness and sophistication toward impermanence) is why his love for her increased. Japanese literature enjoys reading between the lines. Tales has this trend, but it reaches its culmination with Murasaki’s The Tale of Genji where most plot points happen behind the scenes and with what isn’t said. However, this indirect way of writing relies on the stand in symbols Tales of Ise helped establish. The moon’s bittersweet beauty (again impermanence returns as a theme) provides another example:

Once a group of friends, no longer very young, where admiring the moon together. One of them recited:

As a general thing,

I take but little pleasure

in praising the moon.

Does not its every circuit

make us a little older?

Throughout The Tale of Genji the moon appears. Beyond the beautiful scene it allows Murasaki to describe, it also points to how fleeting the moments are for Genji, just like the above poem suggests for the friends. All of these interwoven references to symbols and other works makes literature interesting and complicated. Of course, English literature does the same. Every culture has its set of symbols and cliches that can make reading difficult unless you understand the linkages. Really, it is little different from how anime and manga are self-referential.

Once there was a woman whose husband had neglected her for years. Perhaps because she was not clever, she took the advice of an unreliable person and became a domestic in a provincial household. It happened one day that she served food to her former husband. That night, the husband told the master of the house to send her to him. “Don’t you know me?” he asked. Then he recited:

Where is the beauty

you flaunted in days of old?

Ah! You have become

merely a cherry tree

despoiled of its blossoms.

The woman was too embarrassed to reply. “Why don’t you answer me?” he asked. “I’m blind and speechless with tears,” she said. He recited:

Here is a person

who has wished to be rid

of her ties to me

Although much time as elapsed,

her lot seems little improved.

He removed his cloak and gave it to her, but she left it and ran off–nobody knows where.

Unlike the medieval romances, I have the distinct impression many of the anecdotes, such as the above, happened. Tales of Ise appears to be a mix of fiction and true events. It provides an interesting view of Japanese culture and court sensibilities at the time. These sensibilities are similar to the the sensibilities of medieval (especially French) romances. Tales of Ise doesn’t feel as fresh and immediate as the works of Sei Shonagon or Lady Nijo or the Gossamer Lady. The collection is more melodramatic to my modern eyes than the works of Japan’s great female writers. However, Tales of Ise remains interesting and readable with its glimpses of how people lived in the Japanese courts during the late 800s and early 900s.

References

Craig McCullough, Helen (1990) Classical Japanese Prose. Stanford University Press.