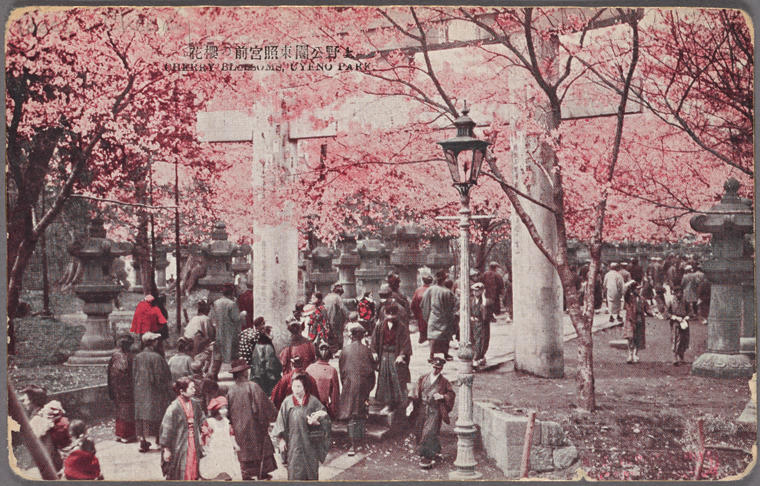

The Heian period (794 to 1185) imported many ideas and conventions from China. This marked the flowering of Japanese ideals of beauty, from Cherry Blossom Viewing Festivals to poetic conventions. It imported Confucian ideals, Chinese writing conventions, Chinese literature, and many other cultural imports that would take on a distinct Japanese flavor. Buddhism also spread throughout Japan. During this time, the Fujiwara clan held the power behind the Imperial Throne.

The Heian period also marked, at least among the nobility, a shift in sexual politics. We really don’t know if people followed the literature and early law codes or if the literature acted as entertainment and the law as an unlived ideal. We also know little about the commoners; we can only go by the scattered accounts and the surviving literature to get an imperfect idea.

Early in Japanese history, women held a lot of influence. Mound burials during the 4th century point to women acting as chieftains and shamaness leaders. These women were buried with iron weapons, mirrors, and jade. When they were buried with their husbands, the women had more jewelry and other grave goods, showing how their social rank was higher than their husbands (Allen, 2003).

In fact, the story of Princess Okinagatarashi, better known as Empress Jingu, point to this. Found in the Kojiki (Records of Ancient Matters) and in Nihon Shoki (History of Japan) she directed the invasion of Korea around the 4th century (Allen, 2003). She ruled as the regent to her son, Emperor Ojin, after the death of Emperor Chuai, but according to accounts, she remained in power even after her son took the throne. She died at the age of 100, likely serving as the regent for her grandchildren.

Allen (2003) writes:

Since their tombs include weapons and armor, it is possible that female rulers of the fourth century led troops. Even in the Hayato Rebellion that arose in Kyūshū in the early eighth century, shamanesses went to the front line to consult the oracles, to inspire the soldiers and to curse their enemies. In Okinawa, head shamanesses led troops in time of war even up to the Middle Ages. This, it would not be surprising if a priestess ruler of the late fourth century led her troops in male attire in response to the needs of the age, as depicted in the story of Jingū.

Before Jingu, brothers and sisters often shared rule. The sister took on the spiritual role (which was more important) while her brother took on administration roles. However, by choosing her son as the inheritor of her spiritual position instead of a daughter, Jingu combined the paired roles. This opened the door for the changes that continued through the Heian period.

By the 5th century, male chieftain burials began to appear, and by the 8th century, female rule had eroded. Women continued to take the throne whenever their husbands died and their sons were too young to rule (Allen, 2003). But the sexual politics had shifted toward what would eventually lead to the male-dominated society of the Edo period.

Heian Rank

By the Heian period, women could still own and inherit land, but they had lost their social rank among the nobility. They no longer enjoyed the wealth streams that allowed the rich burials of the 4th century. Instead, men enjoyed the wealth streams based on their social rank, but they were essentially homeless while women had homes and estates but no wealth to maintain them (Sprague, n.d.). Women were excluded from the elaborate imperial bureaucracy and its income streams.

Speaking of the bureaucracy, the Yoro Code of 757 created 9 ranks with rank 1 as the highest. Each rank had a senior and junior position. Ranks 4 to 8 were further divided into upper and lower senior and upper and lower junior levels, making 16 positions within the ranks of 4 to 8 (Sprague, n.d.). In addition to this, men belonged to one of three groups:

- Kugyo: senior nobles

- Tenjobito: courtiers

- Jige: gentlemen of lower rank

Rank was awarded based on his father or grandfather’s rank and whether or not his mother was the principal wife. Yes, men could have multiple wives, and this related back to the separation of land and wealth among men and women.

Housing Arrangements

Nobleman were essentially homeless, and women were expected to provide a home for her husband. In fact, her family determined his social status more than the rank awarded to him through his father or grandfather. Marriage remained a contract between families (at least in the case of the principal wife) that focused on mutual gain (Grubits, n.d., Sprague, n.d.) This isn’t to say couples didn’t marry for love, but such love marriages still needed to be arranged by the family leaders.

A husband relied on his father-in-law for political support when he moved in with his wife. Because of this, daughters were preferred over sons. A man who had daughters was in a better position than a man who had many sons. A son would never become the emperor, but a daughter may become an imperial consort and even the mother of an emperor (Grubits, n.d.).

The reliance of a man on his wife and her family for his social standing opened the common practice of multiple marriages and affairs found throughout Heian literature. A second wife was often taken for love or if the principal wife failed to have children. But second wives also provided more social contacts inside the rank system. A dallying husband could bring back the benefits of these contacts to his principal wife’s family (Grubits, n.d.). He would spend most of his time living with his principal wife while sometimes traveling to live with his second wife. His income stream, based on his social rank, was expected to maintain both residences, but he still wouldn’t own the properties. As Michinaga Fujiwara wrote in Eiga monogatari: “a man’s wife makes him what he is.”

Marriage, Affairs, and Courtship

Beauty and the arts characterized the Heian period. Much of this creative effort tried into this elaborate system of marriage and affairs. Affairs, as long as they were conducted within the rules, were considered fine. The marriage and affair rules allowed for such relationship fluidity because of two tenants the nobility believed (Grubits, n.d.):

- Male desire was natural and uncontrollable.

- Females were irresistible.

Men couldn’t be blamed for their sexual behaviors because of its nature. Likewise, sexually inactive women were considered abnormal and even possessed by evil spirits, such as foxes. Grubits (n.d.) writes:

Because they were perceived to be incapable of resisting desire, men could not be criticised for sexual acts we would not hesitate to call deviant today, such as rape; the uncontrollable nature of desire gave men permission to satisfy their lusts even in an unwilling female. Any violation that occurred was the result of passion, and if anyone was to blame, it was the female for letting her guard down.

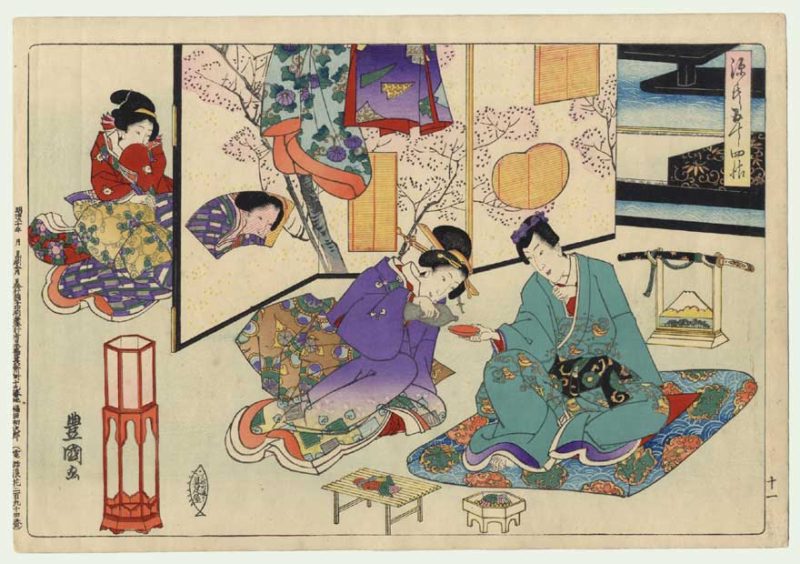

But such actions by men also violated the aesthetic rules that controlled sex and affairs. Men were expected to be poets and woo women, not take them by force. Letters and poems were the main means of courtship. Partners were judged based on their calligraphy, the cleverness of their verses, and the quality of the paper they used. Months would pass before the partners, whether future spouses or affair partners, would see each other (Sprague, n.d.).

Marriage and divorce were not legal practices. Rather, they were social processes governed by the same rules as affairs (Sprague, n.d.). Heian writer Shonagon comments on some of these rules in her Pillowbook:

A lover who is leaving at dawn announces that he has to find his fan and his paper …Finally he discovers the objects. He thrusts the paper into the breast of his robe with a great rustling sound; then he snaps open his fan and busily fans away with it. Only now is he ready to take his leave. What charmless behaviour! “Hateful” is an understatement… A good lover will behave as elegantly at dawn as at any other time. He drags himself out of bed with a look of dismay on his face … he comes close to the lady and whispers whatever was left unsaid during the night … Presently he raises the lattice, and the two lovers stand together by the side door while he tells her how he dreads the coming day, which will keep them apart; then he slips away. The lady watches him go, and this moment of parting will remain among her most charming memories.

Marriage was little more than a groom visiting three nights in a row–similar to what Shonagon describes– arriving at sunset and leaving at dawn. On the third morning, he stayed until he was “discovered” by the bride’s parents and at a special “third day” cake with them (Sprague, n.d.). However, Shonagon also comments on affairs in her list of “Depressing Things:”

With much bustle and excitement a young man has moved into the house of a certain family as the daughter’s husband. One day he fails to come home, and it turns out that some high-ranking Court lady has taken him as her lover. How depressing! “Will he eventually tire of the woman and come back to us?” his wife’s family wonder ruefully.

The Shift of Sexual Politics

Affairs appear throughout Heian literature, including the Tale of Genji, The Pillowbook of Sei Shonagon, and The Gossamer Years. Much of it came from the ideals of beauty and transience that the nobility followed and the social system the Yoro Code imposed. But as the Heian period neared its end, the military class took over from the indulgent nobility, plunging Japan into the Genpai War and toward the rise of the Kamakura Shogunate. While women would still wield influence, they didn’t wield it as Empress Jingu had or even as the Heian women had. By the time the Edo period arose, women could no longer own property nor did they have the sexual freedom they had during the Heian period.

References

Allen, Chizuko (2003) Empress Jingu: a shamaness ruler in early Japan. Japan Forum 15 (1) 81-98.

Grubits, Matthew (n.d.) Things that are near though distant: extramarital affairs in Heian-Period Japan. New Voices 3.

Morris, Ivan, trans., The Pillowbook of Sei Shônagon. London: Penguin Books, 1971.

Sprague, April (n.d. ) Writing the irogonomi: sexual politics, Heian-style. New Voices 5.

Appreciate the source references. Recently, I had a conversation detailing how the “Women’s Lib” movement doesn’t really work in Japan because of the power that is inherent in their position as women. Going back in time (to the Heian Period), we can see the matriarchal spirit in the origin of Japanese society. While times and circumstances have undoubtedly changed in Japan, there has never been any comparison to the circumstances of the women in the west, who have never wielded any real power in their society.

You make a good point. As Japanese women regain social standing in society, Japan would be returning to their oldest traditions. That could be a stick in the eye for those who resist women’s rights by arguing for tradition!