“…there will never be a war with Japan.” –Connie Mack

“…hope every Jap that mentions my name gets shot – and to hell with all Japs anyway.” — Babe Ruth

In 1853, Admiral Commodore Matthew Perry forced Japan to open to the United States. Just 20 years later, baseball crossed the Pacific. Japan has not quite been the same since.

An American professor named Horace Wilson taught his students at Kaisei School (we know it now as the University of Tokyo) how to play baseball. It immediately took off. The one-on-one fight between the pitcher and batter had the same dynamics as sumo and martial arts. The discipline of the game also resonated with Japan’s history of samurai code, bushido (Kelly, 2009; Gripentrog, 2010).

Early American-Japanese Baseball

The first US-Japanese baseball game was between Ichiko, Tokyo’s first elite prep school, and the American residents of the Yokohama district in 1896. The Japanese school practiced baseball for 10 years before playing the Americans. The schoolboys trounced the Americans. Two more games ended with the Japanese boys winning. Word of these three games spread and the students and their club became national celebrities. Keep in mind, that during the time, Japan was reworking the treaties the West forced upon it. Beating the Americans in their own game was a big deal for a nation that felt poorly treated. The Higher School team went on to play 13 games over the next 8 years. They only lost to the Americans twice (Ishii, 2004; Kelly, 2009). Beating the Americans at their own game drew the attention of the nation. The Japanese obsession with baseball started.

Baseball in the late 1800s and early 1900s was thought to embody all that was America: democracy, can-do spirit, and individual merit. The fact that Japan was so enthusiastic about the game, gave Americans the feeling of a special relationship with the Japanese compared to countries that did not share the passion for baseball (Gripentrog, 2010). Because the Japanese were so good at baseball, Americans felt like Japan was fertile soil for American values. This idea continued right up until the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Major League Baseball toured Japan in 1931 and 1934 to much fanfare. While the Japanese tour of 1935 was much quieter in the states, it still positively impacted American perception of Japan (Gripentrog, 2010). The shared love of the game gave many people heady feelings that baseball could promise permanent friendly relations between the two countries.

In 1934, Connie Mack, a famous baseball player and team manager, was so impressed with Japanese baseball fans that he could not see any way for American to go to war with Japan. Babe Ruth experienced what it was like to be a Japanese superstar during the 1934 tour. He spoke favorably of Japanese baseball fans (that is until Japan attacked the United States). The emotional highs of the game even made US diplomats take notice. Joseph Grew, the US ambassador to Japan in 1932, commented that Babe Ruth was a more effective ambassador than he could ever be (Gripentrog, 2010).

The popularity of American players defied belief. As popular as Lou Gehrig was at home, he was even more so in Japan. Where ever the All Stars went, stadiums sold out. Lou Gehrig could not describe just how enthusiastic Japanese baseball fans could be because he would be accused of exaggerating:

“I have seen some excited crowds in baseball, but

nothing before like this. I do not know of anything in my entire career that has touched me as much as this welcome. It seemed like something out of a dream….My first thought was that I only wish ‘Mom’ and ‘Pop’…could have seen it….It will be difficult to try to give a description of it to any of the fans and players in America. They all will think you are exaggerating.”

During the Japanese tours, Americans found Japanese politeness amazing and reinforced the favorable views American had of Japanese. The Tokyo Giants had a habit of removing their hats and bowing to the umpires (Gripentrog, 2010).

Baseball’s Role in Rebuilding Japan after World War II

The attack on Pearl Harbor completely changed the American attitude toward the Japanese. American media quickly shifted toward dehumanizing the Japanese (Sporting News, 1941):

[Japan] was really never converted to baseball….[The Japanese] may have acquired a little skill at the game, but the soul of our National Game never touched them. No nation which has had intimate contact with baseball as the Japanese could have committed the vicious, infamous deed of December 7, 1941. if the spirit of the game ever had penetrated their yellow hides.

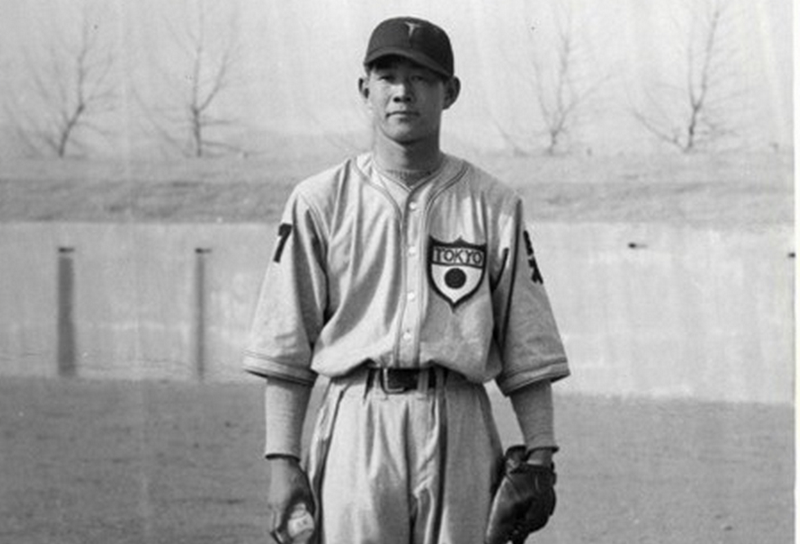

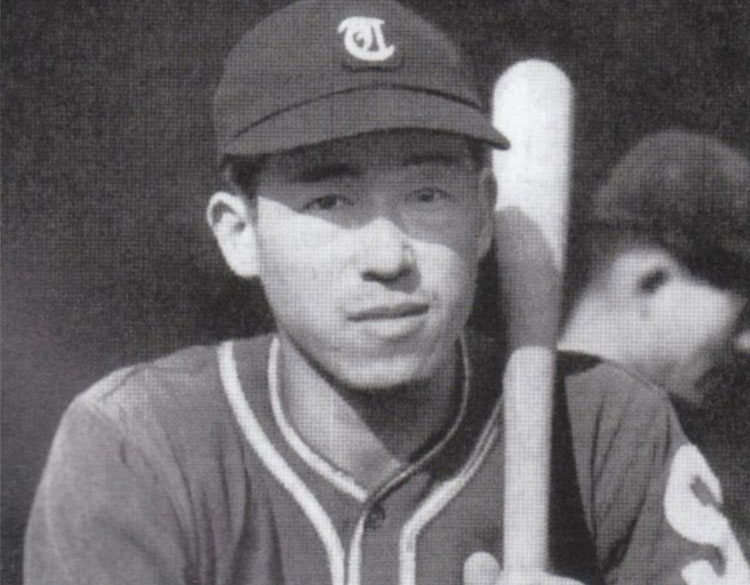

On Japan’s part, the government banned the use of English words, including baseball. It also banned the game altogether, and many great Japanese baseball players died in the war. Eiji Sawamura, the Japanese pitcher that struck out both Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, died. Oddly, Japanese prisoners of war in Soviet Union and American camps kept the game alive (Ishii, 2004).

After Japan’s surrender to the United States, Supreme Commander of Allied Powers Douglas MacArthur recognized how the game could help American-Japanese relations. He revived both baseball and sumo. Nine months after the surrender, professional baseball returned. MacArthur tapped the language of the 1930s. Baseball proved to be a democratizing influence after all.One Japanese team even selected their manager by popular vote. Also shared interest in the sport, and the positive history of the sport before WWII proved too powerful for the negative sentiments Babe Ruth would utter during the war (Whiting, 1986; Gripentrog, 2010).

The relationship baseball forged between the US and Japan continues. It is not unusual to see Japanese and American players in either country. The MLB sends All-Star teams to Japan every other year (Ishii, 2004). The shared interest in baseball is unique. The US and Japan both call baseball their national pastime. Baseball was certainly a major factor in the acceptance of Japanese exports like anime and manga today. Likewise, baseball did much to smooth other problems Commodore Perry caused in early Japanese-American relations. Finally, baseball also helped Japan democratize after World War II. It also helped improve the view each country had for each other.

Why Did Baseball Become Popular in Japan?

In 1900, Inazo Nitobe wrote Bushido: The Soul of Japan. This book associated the samurai class of the past with certain ethics. These ethics had parallels with how Japanese started to view baseball (Kelly, 2009). The book, baseball, and the political factors of the time all mixed together to create the idea of “the Way of Baseball.” Many in Japan viewed bushido as the core of what it means to be Japanese. Mix that sense of identity with baseball, and it is obvious why the sport took off.

After all, the Japanese were feeling oppressed by the Americans when baseball appeared. And it turned out the Japanese could whip the Americans at their own game. The sense of equality and perhaps even cultural superiority was a heady drug for a culture that felt itself shortchanged. Baseball reflected the increasing militarization of the country. It was a means of asserting Japanese identity.

However, bushido’s ethics were narrowed down to only a certain few and ignored the rest: self-sacrifice being the most prominent. This narrowing of bushido created both the idea of Samurai Baseball and the kamikaze of World War II. Other philosophies also competed in baseball, but the militarization of the time supported the idea of samurai baseball. Ironically, despite how baseball made it easier for the Japanese military to indoctrinate people into their cause, baseball was banned during WWII.

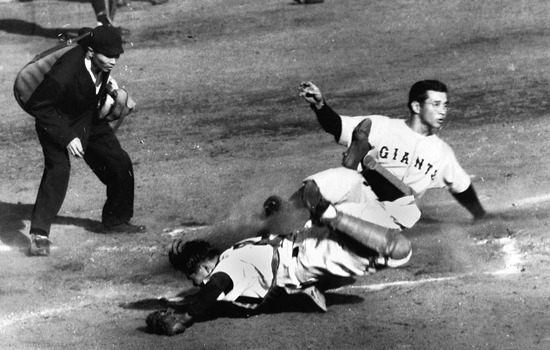

Samurai Baseball

The idea of samurai baseball became both a means of propaganda and of profit. In the 1960s, corporate samurai baseball became dominate. The Yomiuri Giants, owned by the Yomiuri conglomerate, one the national championship for 9 years in a row. The popularity of the players and the team, assured by the Yomiuri company, created a new type of baseball in Japan. Of course, this corporate backing was already common in the United States. The Giants came to represent the confident, industrious Japanese society and the shifting Japanese cultural values. The idea of samurai baseball became a caricature rather than a sports philosophy. Profit drove the change. Now samurai armed with briefcases were supposed to draw inspiration from samurai armed with baseball bats. The media pushed the image (Kelly, 2009).

Baseball has an interesting place in American-Japanese relations. For all but 20 years, Japan and the United States shared the game. Baseball served as an outlet for pent up feelings of being short changed by the United States, particularly after being forced open by Commodore Perry. Common interest in the sport allowed Japan and the United States to quickly rebuild their relationship after World War II. In fact, baseball was used as a democratizing force by MacArthur.

The shared love of baseball is something unique to Japanese and American relations. It is common for us to see players with Japanese names and for the Japanese to see American players. Baseball is one of the many reasons why Americans and Japanese share an affinity for each other.

References

Ishii, J. (2004). The History of the Baseball Partnership across the Pacific Ocean. Embassy of Japan. http://www.us.emb-japan.go.jp/english/html/embassy/otherstaff_ishii0314.htm

Kelly, W. (2009) Samurai Baseball: The Vicissitudes of a National Sporting Style, The International Journal of the History of Sport, 26:3, 429-441, DOI:

10.1080/09523360802602299

Gillespie, P (2011). History of Baseball: The Man from Maui. http://fromdeeprightfield.com/history-of-baseball-the-man-from-maui/

Gripentrog, J. (2010). The Transnational Pastime: Baseball and American Perceptions of Japan in the 1930s. Diplomatic History 34 [2] p. 247.

Sporting News, (1941). “It’s Not the Same Game in Japan,” December 18, 1941, 4.

Whiting, R (1986). East Meets West in the Japanese Game of Besuboru. Smithsonian. http://japanesebaseball.com/writers/display.gsp?id=43627