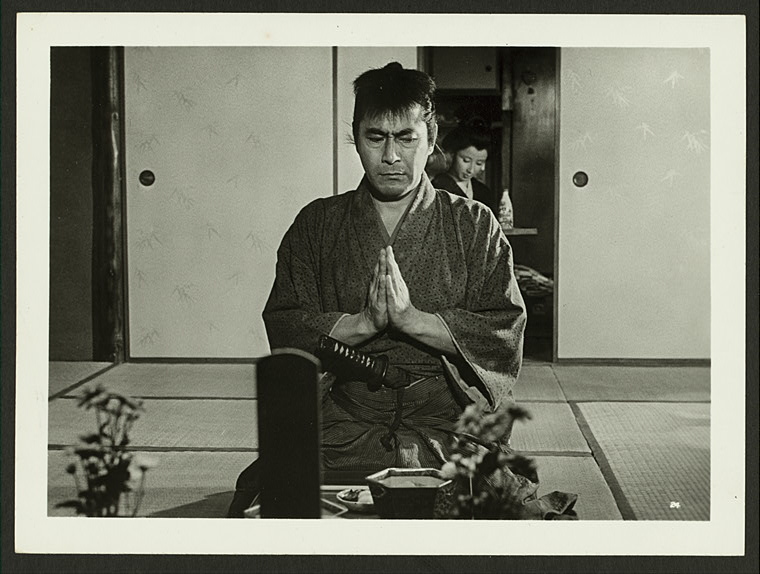

Miyamato Musashi’s work “The Way to be Followed Alone,” or Dokkodo, is the samurai’s lesser known work next to The Book of Five Rings (Gorin no Sho). Musashi is a ronin, or masterless samurai, and considered to be the best samurai who lived.

Musashi was born around 1584. His father was named Hirata Munisai, and his mother was called Omasa. However, his mother died shortly after he was born. His father married Yoshiko, who would raise him. Musashi is best known for winning over 60 duels. He founded a martial arts school where he built upon the fighting techniques his father taught him. Beyond being a warrior, Musashi also wrote, sculpted, painted, and practiced calligraphy. He was something of a Japanese Leonardo da Vinci. His brushwork was bold, and often blended the subject and background together. His brushwork reflects his philosophy that strategy, as he called his approach to swordsmanship, was inseparable from everyday life. His swordsmanship reflected in his bold writing and brushwork, and his bold writing and brushwork reflected in his swordsmanship. As far as we can tell, he began to combine intellectual arts and physical arts together at a young age, no doubt influenced by his father. Unfortunately, we know little about Munisai.

Musashi’s masterpiece, The Book of Five Rings still offers lessons for those who practice martial arts. However, it proves to be a difficult read, especially if you don’t practice kendo or other martial arts, which is why I haven’t covered it on JP. I’m not a martial artist, so The Book of Five Rings proved to be quite abstract for me. Converting actions best learned through practice and motion into words makes the book a little vague or garbled at times. However, “The Way to be Followed Alone,” which was written around the same time–at the end of Musashi’s life–is a list of tenets. Dokkodo, as I will call the work from now on, provides useful advice for everyone, not just martial artists. Musashi often wrote in ways that forced us to think deeply. He often admonishes us: “You should examine that well,” and “This must be worked out.” Such phrases tell us we need to experience what he writes for ourselves in order to understand. Considering Musashi often wrote about how to perform a strike or some other physical move, this makes sense. But it also makes sense for ideas as he presents in Dokkodo. Some ideas can be comprehended by reading but only understood through application. Meditation provides a good example. You can read about it all you want, but until you actually practice meditation, you can’t understand it.

In any case, let’s look at the 21 tenets of Dokkodo as translated by Tokitsu Kenji (2004). I will explain how I understand each one, but remember you too need “should examine that well.”

Do not go against the way of the human world that is perpetuated from generation to generation.

Musashi isn’t telling us to follow the crowd. Rather, he refers to following wisdom people have accumulated over the ages. The original Japanese, according to Tokitsu (2004), denotes movement with its repetition and how wisdom transcends time.

Do not seek pleasure for its own sake.

Here, Musashi isn’t saying pleasure is wrong. Rather, seeking pleasure is. Musashi suggests pleasure gained as a side effect, such as the pleasure of learning something new, is fine. However, chasing pleasure, as warned in most of the world’s wisdom traditions is destructive. This ties back to Musashi’s first principle of heeding tested wisdom.

Do not, in any circumstance, depend upon a partial feeling.

“Partial feeling” refers to a feeling of partiality, of a preference. Musashi urges us to beware feelings of dependency, partiality, and egotism. Favoring yourself is an act of partiality. Instead, we need to be clear-sighted and beware our innate biases.

Think lightly of yourself and think deeply of the world.

Thinking lightly, today, means “don’t take yourself seriously.” This idea doesn’t quite go as far as Musashi intends. Musashi is warning us not to put ourselves at the center of life, to not think much of ourselves. Have you ever gazed at the night sky and considered how vast the universe is? How you are smaller than an atom in the scope of the universe. That deep thinking is what Musashi points to here.

Be detached from desire your whole life long.

Musashi channels many Buddhist ideas in his writing. This is one of them. In Buddhism, the root of suffering is attachment to our misconceptions. To put it simply, desiring and not having makes us suffer. By letting go of desires and accepting reality as it is, painful or not, we reduce our suffering.

Do not regret what you have done.

This ties back to the idea of detachment. Regret involves holding onto something: mistakes, lost loves, whatever it is. It causes suffering. Letting go and realizing mistakes and endings are learning experiences help remove regrets.

Never be jealous of others, either in good or in evil.

From here on, Musashi keeps building on the idea of detachment. Jealousy is wanting what others have or holding onto what you do have. It is the result of desire or attachment.

Never let yourself be saddened by a separation.

All relationships end. Death separates us from everything and everyone we love. Musashi urges us to accept this reality. The Roman writer, Seneca, also speaks of this: “We should love all our dear ones… but always with the thought that we have no promise that we may keep them forever—nay, no promise even that we may keep them for long.” As a ronin Musashi was often separated from people he cared about.

Resentment and complaint are appropriate neither for yourself or for others.

This makes me think of Marcus Aurelius: “Don’t be overheard complaining…Not even to yourself.”

Do not let yourself be guided by the feeling of love.

Musashi dedicated himself to his strategy. We don’t know if he had any lovers, but evidence points to a solitary life. Love can extend to objects, which Musashi warns against.

In all things, do not have any preferences.

I struggle with this idea. Having a preference, having an opinion, is the American way! But most of our preferences and opinions are not based on evidence or reality. They build on emotions which are unreliable. Not having a preference means we have to have an open, clear mind that can examine reality as it is without opinion. It means we entertain ideas without favoring or disliking them. This is a hard idea to practice, especially when you live in a polarized country like the United States.

Do not have any particular desire regarding your private domicile.

Don’t desire to live in a certain house or place. As a famous traveler, Musashi had slept in rich rooms and under bushes. At the end of his life, he owned a nice home, but he wrote The Book of Five Rings and Dokkodo in a cave.

Do not pursue the taste of good food.

This ties back to pleasure. Good food is fine, but don’t chase after it. The adage especially rings in our age of obesity.

Do not possess ancient objects intended to be preserved for the future.

Musashi didn’t believe in collecting. Again, this ties back to the idea of attachment and the reality of our uncertain futures.

Do not act following customary beliefs.

This might be better phrased “Don’t follow superstitious thinking.” We can also read this as a warning against groupthink, although that is stretching what Musashi had intended. Groupthink includes ideas that people take for granted, and these ideas always need to be examined for ourselves. Musashi urges us to think and act for ourselves rather than follow the norms of a culture. Culture often influences our thinking without our awareness. Musashi tells us to be aware and act in ways that are true to ourselves rather than follow society or our in-group culture.

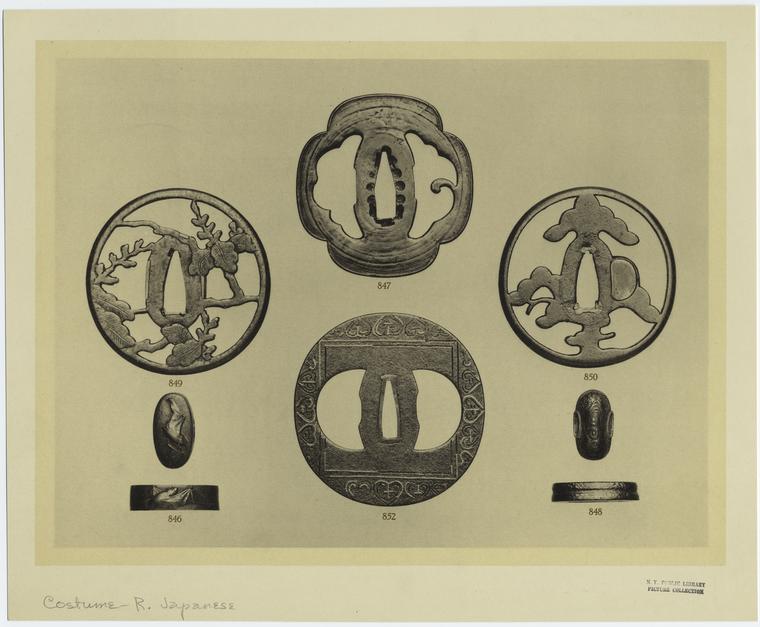

Do not seek especially either to collect or to practice arms beyond what is useful.

Here is the warrior Musashi at work. Collecting weapons or practicing with them beyond what is needed for self-improvement isn’t a good practice. This saying warns us to keep to what furthers our goals.

Do not shun death in the way.

This adage combines the Buddhist idea of nonattachment to life with the samurai ideal of embracing death (often to avoid it in the process). For a samurai, shunning death often led to death. It prevented a samurai from acting in ways that would have saved his life instead. Likewise, Musashi reminds us that death is always with us on the path of life.

Do not seek to possess either goods or fiefs for your old age.

Musashi spent the last years of his life living in a cave. I would rather live comfortably in my old age, but he is warning about focusing our energies too much on material things. Musashi is a minimalist that calls for a balance of living in the present and thinking of the future. Musashi was concerned about his strategy surviving him despite this rule, for example.

Respect Buddha and the gods without counting on their help.

Musashi believed in personal responsibility and taking action rather than waiting on divine providence.

You can abandon your own body, but you must hold on to your honor.

Samurai believed honor was more important than life. Honor came from your actions.

Never stray from the way of strategy.

Musashi’s way of strategy includes these tenets in addition to swordsmanship. He tells us to keep at it. This level of dedication, of commitment that lasts throughout life, is a rare thing in the modern world. Musashi dedicated his entire life to the sword. His writing and art were another means of practice. Dedicating your entire life to one practice, to truly master it, is a hard, endless path.

Dokkodo is an interesting list that encapsulates the ideals found in The Book of Five Rings and Musashi’s other writings. This list appears simple, but applying the ideas to your life is challenging. Not having a preference is especially challenging for me. I am often opinionated and over-estimate how well-thought those opinions are. If I didn’t have a preference, I would be more open to new information and also see my own flawed thinking processes.

As you can see, Musashi was more than a warrior. His writing focused on putting physical motion into words so his two-sword fighting technique could be passed on. “The Way to the Followed Alone” provides an overview of the insights his martial arts and life taught him.

Soon after writing Dokkodo, Musashi died. It was 1645. He was 61 years old.

References

Tokitsu Kenji (2004) Miyamato Musashi. His Life and Writings. Boston: Weatherhill.

Harris, Victor. trans. (2018). The Book of Five Rings. Arcturus Publishing.