Censorship of anime nudity isn’t subtle (As you can guess, I’m going to discuss nudity and include images some may find troubling). Streaks of white light or darkness slash across character’s “naughty” bits. A lady’s long hair stick to her nipples as if they are made of glue while the rest of her hair flutters in the breeze. Perhaps the most common censorship involves the animators simply not drawing the nipples of guys and girls. Ironically, censorship methods draw more attention to these parts. In fact, censorship can make an innocent scene sexual. This becomes particularly thorny when dealing with child characters.

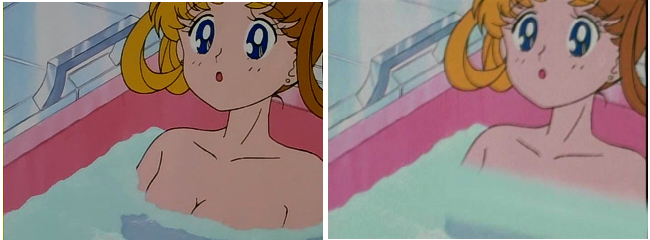

A few scenes of Made in the Abyss has caused a stir. Riko, a 12-year-old girl, appears in these scenes without a shirt. However, the scenes are not sexual, and they are already censored by her long hair. Yet, because she is under age, her nudity causes a problem for many people. Let’s look at a still from one of the scenes, the original and one that I’ve censored using a common censoring method in anime.

In the unedited scene, Riko expresses innocent joy in her pose, but as soon as I censored the scene with the white light streak, the scene loses its innocence. Censorship implies there is something wrong or taboo about whatever is being censored. In the original, you see a slight bulge of her budding breasts, but the context and her pose doesn’t make this sexual. Her expression of hapiness and her open pose expresses an unawareness of her nudity. Nudity and nakedness differ. Nakedness involves the awareness of being seen by other, and it’s associated with voyeurism, humiliation, vulnerability, or shame. Whereas nudity is neutral. It just is (Bey, 2011). Once we censor Riko, her nudity becomes nakedness. We are more aware she isn’t wearing a shirt with the light blocking out her chest. It changes the context.

In the unedited scene, Riko expresses innocent joy in her pose, but as soon as I censored the scene with the white light streak, the scene loses its innocence. Censorship implies there is something wrong or taboo about whatever is being censored. In the original, you see a slight bulge of her budding breasts, but the context and her pose doesn’t make this sexual. Her expression of hapiness and her open pose expresses an unawareness of her nudity. Nudity and nakedness differ. Nakedness involves the awareness of being seen by other, and it’s associated with voyeurism, humiliation, vulnerability, or shame. Whereas nudity is neutral. It just is (Bey, 2011). Once we censor Riko, her nudity becomes nakedness. We are more aware she isn’t wearing a shirt with the light blocking out her chest. It changes the context.

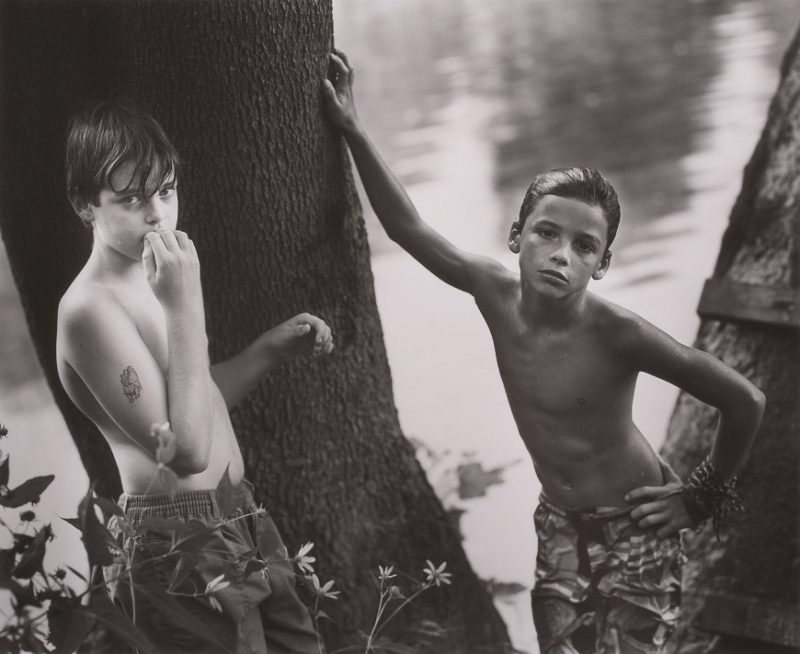

When it comes to child nudity, people’s efforts to avoid anything that can be construed as pornography can make it pornography. The efforts can also run into subconscious racism. When Sally Mann photographed her children in the nude, it caused a stir. She and her family are Caucasian. While adults found the images objectionable, preadolescence students saw them as an effort to show her children as “confident, free, and natural.” They didn’t see the images as pornographic or exploitative as some adults did: “Although these are arguably images of informational nudes which service to illustrate the rural family culture surrounding the artist’s home, the context for viewing, as well as the ethnicity and race of these children plays a large role in their interpretations.” Similar images of black children in National Geographic rarely cause the same discomfort. Child nudity, whether it is in anime or journalism or art, depends on context, and race is a part of that context.

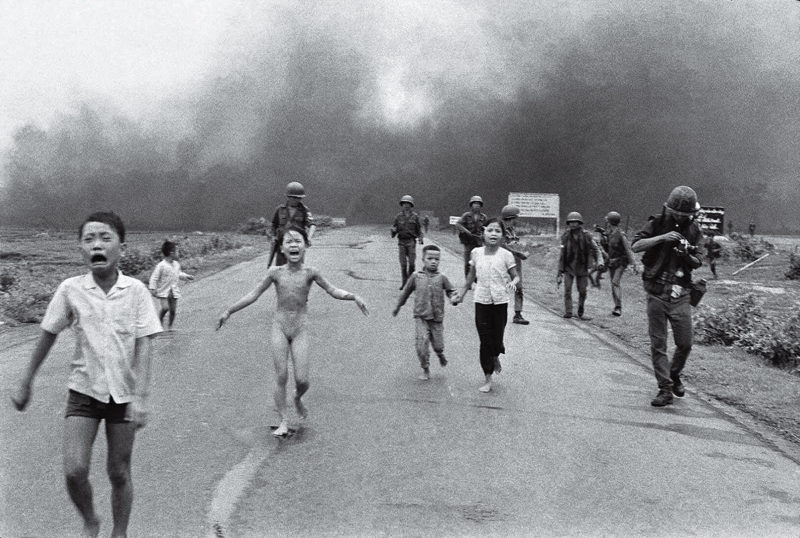

Nick Ut’s The Terror of War photograph from the Vietnam War depicted a 9-year-old girl naked, burned from napalm and sparked various censorship battles, albeit brief, among newspapers at the time and on Facebook in 2016. The nudity sparked the censorship debate, not the violence (Time, 2016). Violence isn’t subject to the same level of censorship as the naked body, no matter the context. However, context determines whether or not nudity is, well, nudity or if it is nakedness. Censorship butts against human arousal responses and objectification. Context often determines the level of objectification. Few can objectify The Terror of War, yet the girl’s nudity made people think twice about running the photo.

The Nature of Sexual Arousal

Sexual arousal comes from a complex mix of your mental and physical state in a given situation. It starts with a state of mind, which is why censorship can cause an arousal response. It can shift your thoughts toward lewd by suggesting something desirable hides behind the pixelation. Imagination, or self projection, plays a critical role in arousal. Both men and women rely on projection when viewing images and films. Women, in particular, project themselves into the context, and the context plays a critical role in her arousal: “Women’s ability to imagine themselves as the woman in the [erotic] film was the only factor the strongly correlated with their reported arousal (Rupp, 2008). ”

Neural studies suggest men are more visually and emotionally selective as to what images they find attractive. Heterosexual men have a strong opposite-sex bias in their reaction (showing disgust toward images of men and attraction toward women) and show selectivity as to what types of images they find attractive. Women in these studies “do not emotionally discriminate between opposite sex and same sex stimuli in the manner than men do (Rupp, 2008).” When you combine this research with censorship practices, it is possible for men to feel attraction toward censored images–which may be why Japanese pornography doesn’t try to get the government’s censorship requirements for genitalia revoked. Women focus on their ability to project into the context regardless of the gender of those involved. On the surface, women appear less effected by censorship. However, this isn’t the case because censorship encourages objectification.

In various studies surrounding clothing and people’s sexual and emotional responses, women have been proven more affected by objectification than men. Clothing itself can objectify women when the fashion sits on the margin of a society’s acceptability. Wearing only swimsuits and underwear increases the chance “a person could be viewed as a mere body that exists for the pleasure and use of others (Awasthi, 2017).” Swimsuit-wearing women report feeling more body shame, and women who self-objectify–choosing clothes for fashion as opposed to comfort and her sensibilities–report more depression, sexual dysfunction. eating disorders, stress, and problems socializing with others as an equal. Media has shifted away from male-gaze objectification toward women-centered objectification—the presentation that women choose to present themselves in any way they wish. This creates an “internal self-policing narcissistic gaze” that creates a deeper level of exploitation and objectification compared to even male-gaze objectification. It opens the possibility of deeper media manipulation and self-image problems because they are self-inflicted (Awasthi, 2017). Yet, this ties back into the idea of projection. Women and men project toward being and being with women wearing sexy outfits. That projection creates dissatisfaction for not meeting those objectifying standards. In turn, censorship reinforces those standards by censoring women’s chests and not men’s.

Censorship’s Reinforcing Role

Clothing and censorship draws attention to the body as an object for others to use for pleasure. Of course, in many contexts censorship wouldn’t increase objectification unless the viewer’s imagination is particularly drawn toward censored images. For example, censoring an upskirt camera angle wouldn’t change the objectifying goal of the scene. Although it may excite the imagination of some viewers more than showing the underwear in the first place. Censorship doesn’t prevent men with hostile and aggressive views toward women to objectify women more often than other men (Awasthi, 2017). In sexualized contexts, censorship doesn’t really help. It could even prompt viewers to search for uncensored images of the content, which can increase their exposure to objectifying content. It stimulates curiosity.

Censorship sends the message that female bodies are inherently problematic: sexual, disgusting, wrong.The problem centers on the messages and views people consume. In another word, context. I lay the fault of objectification on those who do the objectifying. The human body is beautiful of itself, but society’s messages has assigned it with negative connotations that censorship only forwards. According to various studies, “[w]omen in provocative clothing are rated as more flirtatious, seductive, promiscuous, and sexually experienced—and as less strong, determined, intelligent, and self-respecting (Awasthi, 2017).” Those views come from society’s collective perspective that feeds the ideas of objectification.

Hiding or forbidding something only encourages people’s curiosity and imagination. It encourages objectification of the female body and even creates a fetish. I stand against objectification, but at the same time, I recognize it isn’t going to end. Sexualized context encourages objectification and projection, yet censoring these scenes as anime does changes nothing about those scenes. Censoring innocent scenes like with Riko taints them with all the objectification that comes with the white streak. Censorship doesn’t protect children because in contexts that use censorship are already sexual. Children simply shouldn’t be watching such content if parents are truly concerned. Censorship defeats its own purpose.

References

Awasthi, Bhuvanesh (2017) From Attire to Assault: Clothing, Objectifiction, and De-humanization – a Possible Prelude to Sexual Violence? Frontiers in Psychology. 8. 338.

Bey, Sharif (2011) Naked Bodies and Nasty Pictures: Decoding Sex Scripts in Preadolescence, Re-Examining Normative Nudity through Art Education. Studies in Art Education. 52 (3) 196-212.

Rupp, Heather & Wallen, Kim (2008). Sex Differences in Response to Visual Sexual Stimuli: A Review. Arch Sex Behav. 37(2) 206-2018.

Time (2016). The Story Behind the ‘Napalm Girl’ Photo Censored by Facebook. Time. http://time.com/4485344/napalm-girl-war-photo-facebook/