Originally the word kimono meant “a thing to wear.” The word was pulled into English during the recent Meiji period (1868-1912) when Western clothing entered Japan. During this time, the Japanese felt the need to name their native dress (wafuku) to contrast it against the western styles (yofuku).

The kimono became the representation of Japanese tradition during the Meiji period. However, wrapping women in “Japanese culture” began as far back as the Tokugawa period (1600-1867) where the ideal Japanese woman began to form in cultural consciousness. This development solidified in the Meiji period almost as a response to the need for Japanese men to fully embrace westernization to succeed economically. The slogan for Japanese women ryosai kenbo, “good wife, wise mother” was coined in this era. Men were defined as rational and active in their gender role. Their role was represented by the Western suit.

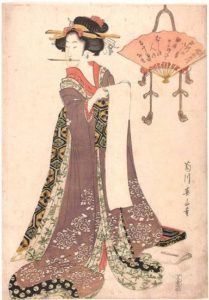

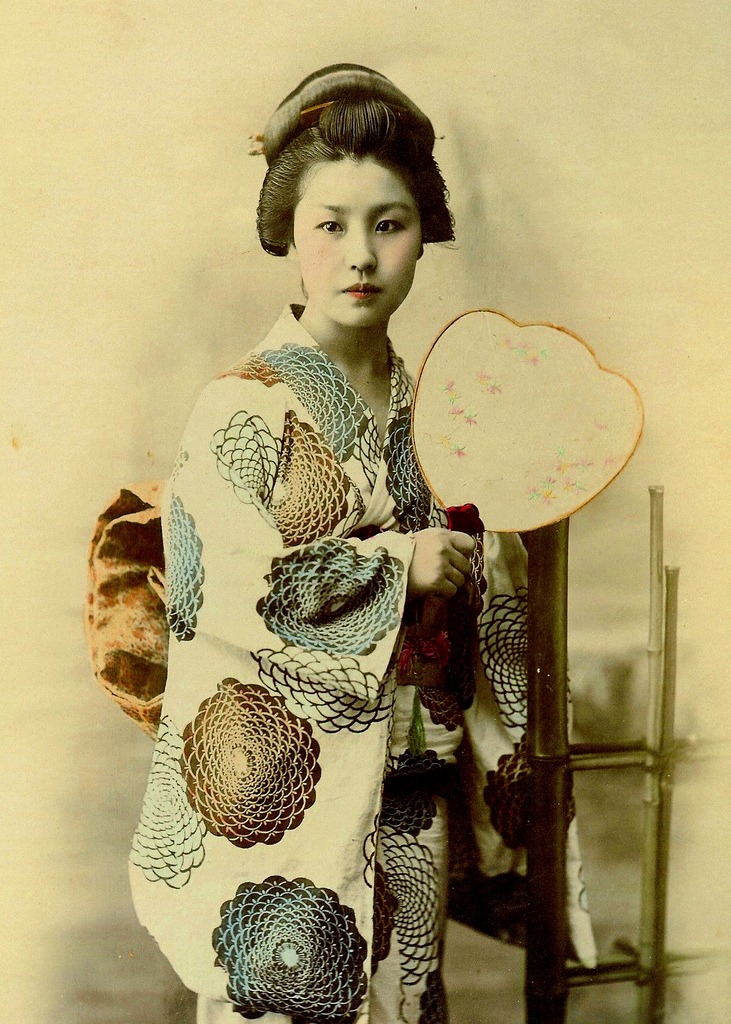

A woman doesn’t wear a kimono. She must be molded to fit the kimono and the aspects of Japanese culture it represents. This requires imperfections to be fixed: boobs are wrapped flat, shoulders straightened, and posture forced to be just so. The kimono forces a woman to walk in a certain way. Sometimes the daughter is wearing the same kimono her mother and grandmother wore. It is a connection to previous generations. Of course, the kimono also is associated with the geisha. The geisha are the living embodiment of Japan: a living book of Japanese arts, music, etiquette and mystery.

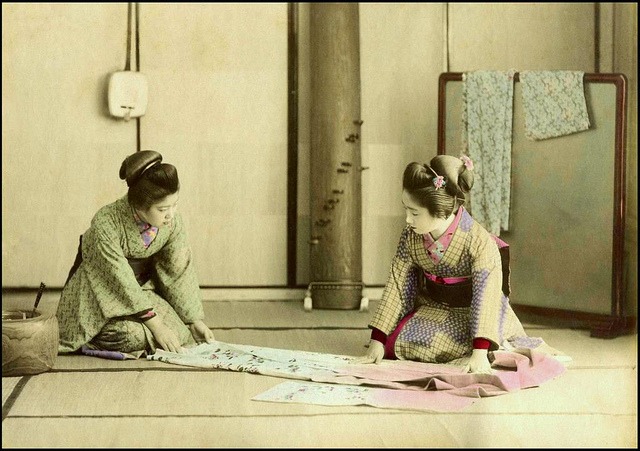

Dressing in a kimono is even an expression of Japanese female ideals. The process requires gambaru (patience) and gamman (endurance). The dressing process is thought to be a way of elders to ritually pass on the ideals of Japanese femininity. Unlike Western dress, the kimono becomes a part of one’s skin because of the different feeling and motion the garment forces on a woman. Some of this has to do with Japanese advertising emphasizing the “natural” desire of girls to wear a kimono (this is called akogare).

Finally, the kimono is a way of preserving many aspects of Japanese culture that could be lost. The art of wearing a kimono encompasses many arts and traditions that have no other way of being passed down. Kimono kitsuke preserves etiquette and traditions that only the geisha would otherwise protect.

Deciding not to wear or how to wear a kimono is an expression of how one views tradition and national identity. Kimono can be personalized or traditional.

What do you think of kimono? Have you had the opportunity to wear one?

References

Assmann, S. (2008). Between Tradition and Innovation: The Reinvention of the Kimono in Japanese Consumer Culture. Fashion Theory. 12[3] p. 359-376.

Goldstein-Gidoni, O. (2001). Kimono and the Construction of Gendered and Cultural Identities. Ethnology. 38[4]. p. 351-370.